Presentation

Bauer’s villa, Libodřice /Kolín/

The Villa in Libodřice near Kolín is one of the outstanding examples of Czech cubist architecture. The family house in cubist style was built in 1912-1914 by a prominent architect Josef Gočár for Adolf Bauer, the tenant and later the owner of the local large estate. In his earlier cubist works designed at the very beginning of 1912 – the House of the Black Madonna in Prague and the spa building in Bohdaneč – Gočár displays vertical and horizontal structural elements.

Contrariwise, the villa in Libodřice shows block stereometric articulation, similar to some unrealized Gočár’s cubist projects, such as e.g. project of a school building in Chotěboř and theatre building in Jindřichův Hradec from September 1912. The final draft of the project of the villa in Libodřice was probably also completed in autumn of 1912. A characteristic feature of the Bauer’s villa is that cubist forms are not limited to decorative star-shaped window edging and skewed form of the main cornice. Gočár intended to give the cubist shape to the entire mass of the villa which is illustrated by combining three polygonal buttresses on the southern side of the building. Spatial arrangement of the house is more traditional, although we can find some cubist details even in the interior.

- History of the Bauer’s villa

- Museum and gallery of cubist design in the Bauer’s villa

- Reconstruction of the Bauer’s villa

- Czech cubism

- Architect Josef Gočár (1880-1945)

History of the Bauer’s villa

The villa is named after its initial owner, landowner of Jewish origin, Adolf Bauer. At first as the manor tenant and subsequently as the owner of farm buildings and lands in the village, Adolf Bauer addressed the then young architect Josef Gočár and had a family house built based on his designs. Bauer had lived in the house with his wife and two daughters until his pre-mature death in 1929. After his death the family probably were not permanently staying in the village, the widow got married again and moved to Prague with her daughters. From 1931 the farm was managed by Antonín Illmann. In 1941 the house was transferred under German economic administration as a result of expropriation of Jewish property and Augustin Juppe, Third Reich’s citizen, settled down there. This administrator was arrested at the beginning of May 1945 and the estate was taken over by the local municipal authority. After introduction of land reform in 1948 the estate fell to the state and was at the municipality’s disposal. Apart from the seat of the local municipal council there was also a library branch and several apartment units in the building. In 1987 the villa was listed as cultural heritage. In 2002 the municipality of Libodřice decided to sell the deteriorating premises. In December 2002 the premises was purchased by the Czech Cubism Foundation with the aim to reconstruct the house and open a permanent exhibition in the reconstructed building – Museum and Gallery of Cubist Design.

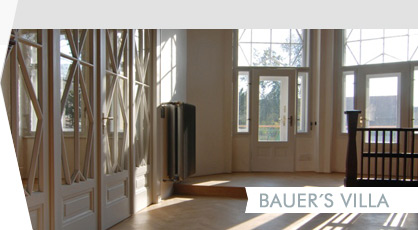

Museum and gallery of cubist design in the Bauer’s villa

The Museum and Gallery of Cubist Design is to be opened to the public after completion of interior works in July 2008.

The villa will be open to the public as an installed cultural monument, offering to its visitors a period atmosphere of cubist interior. Both the exterior and interiors are therefore reconstructed with the aim to match the original shape as much as possible. Preserved elements such as fireplace, built-in wooden closet or bookcase will become the central focus of the exposition, including preserved interior and fittings of the bathroom and technical supporting facilities of the villa. Within the framework of structural and historic survey wallpaper samples have been discovered, based on which replicas are to be produced for the living room, hall and dining room. Interior of the groundfloor will be furnished with period furniture and other art and applied art exhibits from a private collection.

The first floor will house an exposition dedicated to Czech cubism, Josef Gočár and the family of the initial owner of the house, Adolf Bauer. Texts and exhibits will be supported by an audio-visual programme dedicated to the Bauer’s villa and modern architectural monuments in the region. The exposition will be prepared in cooperation with professional and scientific institutions, documentary material will be provided by the National Technical Museum, or more precisely by its Department of Architecture and Structural Engineering.

Reconstruction of the Bauer’s Villa

Reconstruction of the Bauer’s villa involves the structure, interiors as well as technical facilities and equipment.

Interiors are gradually furnished with elements and furniture based on preserved period documents. Our intention is to realize also the original Gočár’s design of fencing. Preserved precious woody plants in the garden will be treated and replenished by other plants and period garden furniture.

| Realized structural reconstruction: | approx. CZK 25m |

| Expected additional investment in interior furnishings and exterior works: |

CZK 10m |

| Commencement of reconstruction: | September 2005 |

| Completion of structural reconstruction: | July 2007 |

| Opening to the public: | July 2008 |

Czech Cubism

The period around 1910 in Europe was associated with the commencement of new avant-garde movements – cubism, futurism, expressionism. Those movements which included also architecture and artistic craft in their programmes usually polemized with excessive rationality and practicality of the previous architectonic modern art style which is said to have neglected more vehement shaping both as regards buildings as well as apartment furnishings, neglecting human spiritual and intellectual needs. In Prague the basis of this new avant-garde became a Fine ArtsGroup, established in 1911 by supporters of Picasso’s and Braque’s cubism - painters Emil Filla, Antonín Procházka, Josef Čapek, sculptor Otto Gutfreund, writer Karel Čapek, architects Pavel Janák, Josef Gočár, Vlastislav Hofman and Josef Chochol.

The group was aware of the epoch-making significance of Picasso’s cubism and attempted to draw consequences from it for their own works in all branches of art work. At the same time, its members - architects - attempted to solve problems faced around 1910 by the entire European architecture and although they felt internally connected to cubist revolution, they did not transfer motives of cubist paintings into their projects and buildings. Cubist artists endeavored to replace rectangular forms of modern art style by skew, broken, pyramidal shapes; they were eager to give box-shaped modernistic interiors a form resembling the inside of a crystal. Painting cubism might have helped them to purify such shape visions and clear them from remnants of earlier modernistic ornaments. However, it was equally important with respect to cubist architects that they believed that their works would be internally in consonance with “subjective” stages of architectural history – particularly with Gothic and radical Baroque – and on top of this, would be able to apply a sensitive approach to the historic environment of Czech towns and cities. Such "cultural heritage-friendly" ability of Czech cubist architecture are illustrated by the Gočár’s House at the Black Madonna in the Old Town, Prague (1912), Chochol’s houses under Prague baroque citadel Vyšehrad (1912-1914) or Janák’s structural modification of the baroque Fára’s house on the square in Pelhřimov (1913-1914).

All cubist architects believed that their new style would give a uniform character to the entire human environment. House and its interior were to become a “comprehensive work of art”, an integral part of which was cubist furniture and lights, cubist coffee and tea sets, vases, doses and ashtrays, cubist images on wallpapers with cubist decorating. For such purpose, in 1912, architects Gočár, Chochol and Janák founded the Prague Art Workshop and designed furniture for the workshop. Minor cubist objects were manufactured by a cooperative named Artěl. This promising start was disrupted by World War I. After the end of war, associated with establishment of the Czechoslovak Republic in 1918, cubism acquired a character of “national style”: broken and crystalline ornaments were replaced by coloured circles and curls. However, international purism and functionalism was round the corner with all cubist architects shifting to this movement in the course of the 1920s. Nevertheless, they left behind one of the most original manifestations of modern European art.

Architect Josef Gočár (1880-1945)

Hardly any other artist could represent modern Czech architecture better than Josef Gočár. His name is familiar even to people who are not interested in architecture. Gočár was a clear winner in a survey recently conducted by the Chamber of Civil Engineers to choose the most important Czech architect of the 20th century.

Even Gočár’s early modernist works dating from 1910-1911 rank among the masterpieces of Czech architecture. They include the Wenke’s department house in Jaroměř and the staircase under the Marian Church in Hradec Králové. As regards both works, Gočár artistically cultivated modern reinforced concrete structure. Broken and crystalline forms decorate the reinforced concrete frame of two of Gočár’s most important cubist buildings, the House of the Black Madonna in Celetná Street in Prague (1912) and the spa building in Bohdaneč near Pardubice (1912-1913). During this period Gočár was also designing cubist furniture, the best examples of which are the furnishings of the architect’s own dining room and bedroom from 1912-1913, or the chandelier and clock created for actor Otto Boleška from 1913.

After establishment of the Czechoslovak Republic Gočár was involved in the birth of the "national style" - its arc-shaped ornaments were intended to express a distinctive nature of Czech cultural traditions and thus represent the new state. This stage of Gočár’s development is represented by the building of Legiobanka in Na Poříčí Street in Prague (1921-1923) or the building of Anglobanka on the Masaryk Square in Hradec Králové (1922-1926). Gočár later designed an excellent zoning plan for this East-Bohemian town and also built several monumental buildings illustrating his shift away from the decorativeness of the “national style” towards a stricter form, resembling the work of Dutch architect Dudok. An honourable place among these works is occupied by the school grounds in V Lipkách Street (1923-1928) or the building of district authorities in Čs. Armády Street (1931-1936), the stylistic expression of which reveals Gočár’s progression towards monumentalized functionalism, similarly as in the Church of St. Wenceslas on Čech Square in Prague (1928-1930).

Gočár never wrote or spoke much about his work. He believed that "who talks too much feels too little". However, he was clearly aware of the fact that his work could be divided in several distinctive style stages. This corresponded to the focus shared by contemporary art historians, who specialized in description of series of styles, studied their evolutionary patterns, and eagerly monitored each change in development of any new work. Among weaker architectural personalities this evoked an illusion that they were only accomplishing transpersonal rules of evolution of a style. Gočár, however, did not let himself to get seduced by this illusion. His works do not stand outside development of the period and document its transformations. Gočár was able to give to each of them a peculiar sign of his unique individuality.

Homepage

Homepage Contact Us

Contact Us